Have you ever wondered why the instrument called the recorder shares a name with a machine that preserves sounds? It’s not a coincidence. “Recorder” is derived from the Latin word recordare, to remember. Centuries before tape or digital recorders were invented, an early version of the the recorder was being used to imitate bird calls. These ancient recorders/bird whistles are the oldest surviving musical instruments, made from the bones of bears and swans and wooly mammoth tusks. One can only speculate why early man found it useful to communicate with birds or recreate their songs.

It makes sense that the flute/recorder was the first musical instrument. One can imagine that an early hominid heard the wind whistling through a hollowed-out bone or tree branch and, awed and intrigued, investigated the phenomenon. They soon discovered that the stronger the wind blew, the tone of the whistle got higher. They then realized that there was an audible pattern to the tones, and that longer and shorter tubes produced different tones. And if there was a hole on the side of the tube that one could cover and uncover with one’s finger, that also affected the tone. The leap from that discovery to the conscious creating of a tube with holes that conformed to the shape of a human hand that, when blown, produced pitches derived from the overtone series (those tones that went higher or lower depending on the strength and speed of the wind blowing through it) apparently happened over 60,000 years ago when Neanderthals built and played such flutes.

Of course, you don’t need a flute or any other instrument to hear the overtone series; you can hear it in your head. Start humming, keep the tone steady, and then slowly open your mouth. You can produce what Pythagoras called “the music of the spheres” with your own voice with no training.

So we see that music is derived directly from nature: the wind makes music, animals make music, natural materials make music with or without modification. In honor of Earth Day, we’ll explore some examples of the way composers have collaborated with nature to create their compositions.

The list of such pieces is vast. Perhaps the best-known example, Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, is celebrating the 300th anniversary of its publication this year. John Banther and I discussed this work at length in Episode 3 of Classical Breakdown. Today, however, I will explore this subject from the perspective of the world’s oldest instrument.

I used the terms flute and recorder interchangeably back in the first two paragraphs. A recorder is a type of flute, after all, and those early bone flutes don’t precisely correspond to either instrument. But as we will see, flutes of all sorts have been used by composers when they want to evoke a pastoral atmosphere, as well as to evoke its original connection to birdsong.

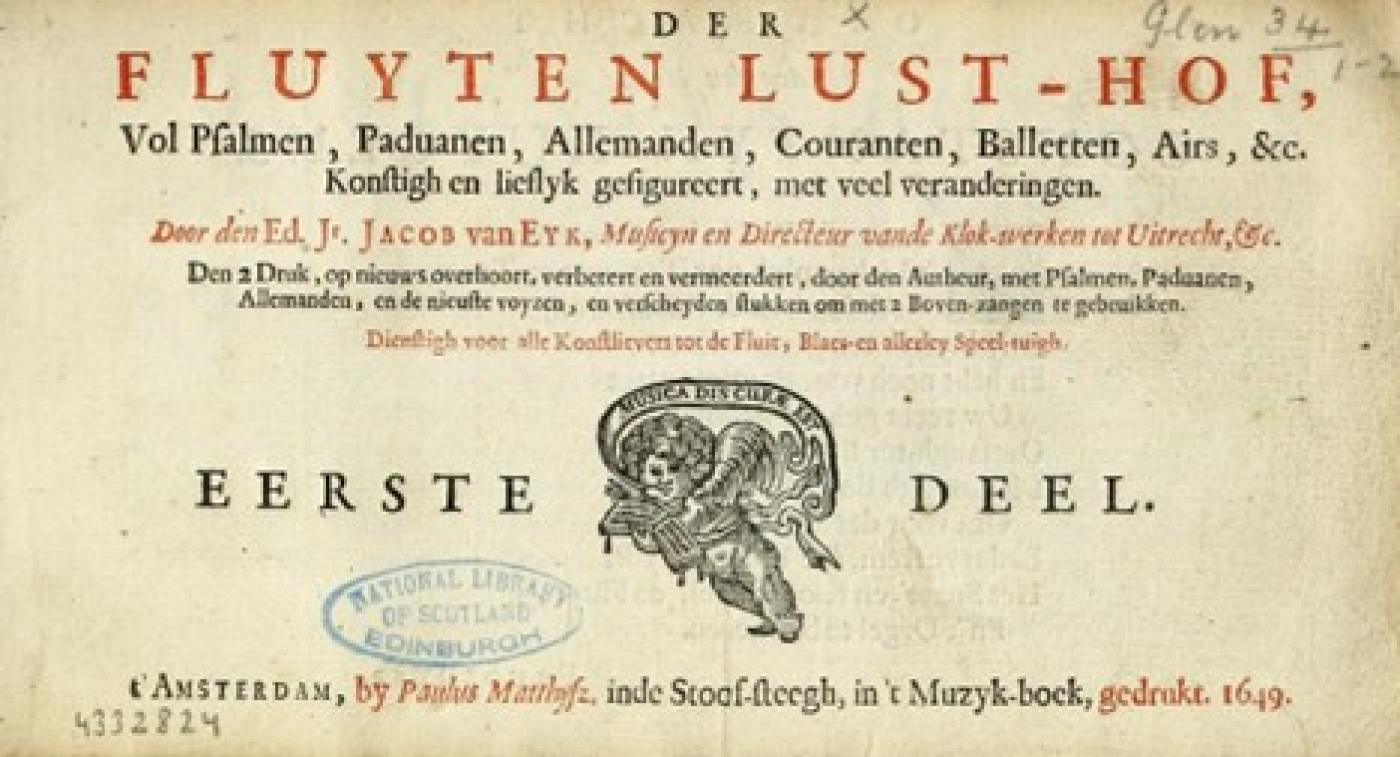

Our first piece is by the 17th century Dutch composer Jacob van Eyck, a remarkable figure who deserves to be better known outside the Netherlands and musicology circles. Blind from birth, he was a virtuoso on both the recorder and the carillon, and he introduced innovations to the design and tuning of the latter that are still used to this day. The only work he published during his lifetime was Der Fluyten Lust-hof (The Flute’s Garden of Pleasure), a two-volume collection of music for solo recorder drawn from hymns, dances, folk songs, and works by composers from all over Europe, all arranged, adapted, and/or elaborated on by Van Eyck, and there are completely original compositions by him in the collection as well. It’s a testament both to the quality of the material and the popularity of the recorder that there were five editions printed between 1644 and 1656. And speaking of music meeting nature: Van Eyck was given a generous stipend by Sint Janskerk in Utrecht to stand in the park outside the church and play tunes from his collection for passers-by. That Van Eyck was well aware of the recorder’s avian origins is evident in a piece that must have been in his outdoor repertoire, Engels Nachtegaeltje (English Nightingale):

You can hear near the end the same five-note theme that Papageno uses to catch birds in Mozart’s The Magic Flute; that may be a coincidence, but it’s not impossible that Mozart was paying tribute to Van Eyck’s own birdsong. And the main tune may sound familiar to WETA Classical listeners because the piece was later adapted for orchestra in the Nightingale movement of a work in regular rotation on our playlists, Ottorino Respighi’s The Birds:

Notice that Respighi replaces the recorder with a flute.

By the 18th century the recorder and flute had developed distinct personalities. The term flute or flauto referred to the recorder, while what we now call the flute was called a traverso or transverse flute, meaning that it was held horizontally and blown across a hole instead of into a fipple that splits the air column. That fipple makes the recorder so easy to get a sound out of that it’s the first instrument we teach to children, while the blowing technique the transverse flute requires makes it one of the most difficult instruments to learn. (Both instruments are hard to play well.) Telemann considered the sound of the two instruments distinct enough that he wrote a double concerto for recorder and traverso, with each instrument displaying its own characteristics, but there were already indications that they would eventually be considered somewhat interchangeable. When Bach revised his Magnificat, he turned the parts originally for recorder into traverso parts, and when he revised his Saint Matthew Passion, he reassigned one passage from two traversi to two recorders, assuming that the same musicians could play both instruments.

And Handel used both instruments to evoke birdsong. In his opera Rinaldo we are treated to a love scene (Act I, scene 6) in “A delightful Grove in which the Birds are heard to sing, and seen flying up and down among the Trees.” According to contemporary reports, trained live birds were actually used in the original production, complementing the sound of three recorders (two altos and a sopranino) as Rinaldo’s lover Almirena sings of the beauty of the nature surrounding her:

While in Handel’s oratorio L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato a transverse flute is used to illustrate the title of the aria “Sweet Bird”, in which the vocalist does her own chirping as well:

If you listen carefully to this astonishing live performance, you can hear actual birds from just outside the window joining in.

This use of both instruments to evoke similar imagery explains why the associations with birds and nature that we see in music for the recorder, the direct descendant of the earliest bird caller, eventually transferred to the modern flute.

In Mozart’s Die Zauberflote both Tamino’s flute and Papageno’s pipes are used to signify man’s benevolent interaction with nature and animals. For Beethoven, the flute had a more personal meaning: “What a humiliation when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing.” This excerpt from the Heiligenstadt Testament, in which he revealed his despair over the realization he was going deaf, offers a clue to how he uses the flute. In the end to the slow introduction to his second symphony, written that same year, we hear a few brief soft bird-like flute solos, in which he seems both to bid farewell to the sounds he loved - he took a lengthy walk in the woods every afternoon - and a determination to keep those sounds alive in his music:

But Beethoven did not just use the flute to evoke gentle birds. In the fourth movement of his five-movement Sixth Symphony, he uses the piccolo to evoke the sound of high winds whistling during a violent thunderstorm:

A little over a century later, in 1913 – the same year that Igor Stravinsky premiered The Rite of Spring, the groundbreaking work for a huge orchestra about the savagery of man’s relationship to nature and his fellow humans - Claude Debussy wrote a much shorter work for a single instrument that was in its own way just as groundbreaking and made a similar statement. Its title, Syrinx, refers to the nymph pursued by the god Pan, who, rather than giving in to his advances, turns herself into a water reed and hides deep within the marshes. Pan cuts down all the reeds to build his pipes, simultaneously killing the object of his desire and transforming them into his main means of expression.

Of course music about nature is really about the human response to it. Sometimes composers make this explicit, as when Beethoven calls the first movement to his Pastoral Symphony “Awakening of cheerful feelings on arriving in the countryside” or when the slow movement of Vivaldi’s Winter corresponds to the lines “Sitting by the fire, passing peaceful, contented days as the rain pours down outside” from the sonnet printed along with that concerto in 1725. Music that celebrates nature is really a celebration of our own capacity to comprehend it. After all, the planet will continue to be here long after humans have passed from it; it will eventually heal itself of the damage we have done to it. So when we say “let’s save the planet” we’re really saying “let’s save ourselves.” All music is a recorder, a remembrance of our emotions as we navigate our environment and our lives, and listening to it reminds us of why life is so precious.

As Beethoven put it in a letter to a woman he loved, Therese Malfatti, who didn’t quite love him back the same way: “How happy I am to be able to wander among bushes and herbs, under trees and over rocks; no man can love the country as I love it. Woods, trees and rocks send back the echoes that man desires.” Beethoven never found a fulfilling romantic human relationship, but nature loved him back.

If you enjoyed this story, be sure to sign up for the WETA Classical Newsletter here for more classical stories delivered right to your inbox.

WETA Passport

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.