During the pandemic we all found different ways of being alone. Violinist Lara St. John’s new album, recorded during the pandemic, demonstrates seventeen different ways for a violinist to be alone.

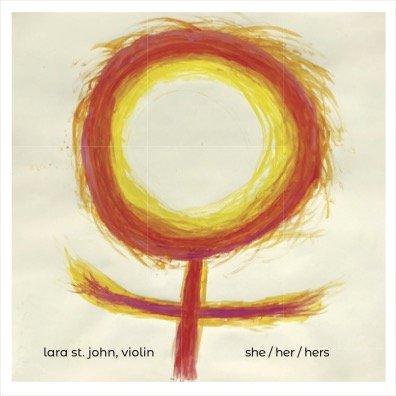

The album, she/her/hers, consists of works by women composers for unaccompanied violin, some written especially for Ms. St. John, some arranged by her, and all written within the last hundred years.

The violin has a long tradition as an unaccompanied solo instrument, whether it's accompanying the folk dances of various cultures or engaging in the counterpoint, both actualized and implied, of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas - which were themselves derived from various dance traditions. Some of the pieces on the album also engage with folk traditions: Milica Paranosic and Ana Sokolović both play with rhythms of the Balkans in their works; Valerie Coleman and Gabriela Lena Frank evoke the songs of Andean South America; and, in one of the three Caprices of hers included in this collection, Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté draws inspiration from the sights and sounds of a Moroccan marketplace.

The challenge for a composer writing for unaccompanied violin is to find ways to have the violin have a sort of conversation with itself so it doesn’t sound lonely - except for those moments when they want to lean into the loneliness. There’s also a sense in which all musicians are self-contained people, masters of loneliness, since they have to immerse themselves in isolation from a young age in order to achieve a high level of virtuosity. (Lara began studying violin when she was two and a half!) And there’s also a kind of historical loneliness inherent in being a woman composer, toiling away at a male-dominated endeavor that still struggles with systemic misogyny.

I wondered if the fact that Lara began when she was so young, and therefore had to deal with the loneliness of the practice room since before she could remember, colored her relationship with her instrument and affected how she coped with isolation as well as with how she approached playing unaccompanied works. She was kind enough to answer my rambling questions in written form.

Lara St. John: I don’t entirely recall the very beginning, but music itself was always somehow innate. I have vivid memories of my mom coming to school with sandwiches and taking us to the basement – I would eat while my brother had to practice and vice-versa. Outside, I could see the kids’ feet at recess playing and having fun, and to this day I can’t stand basements.

Performing alone is liberating, because one is only responsible for oneself. Having the entire work to make your own is not something we fiddlers get to do all that often. For me, it’s a feeling of power, of control over the entirety of what I want the work to say. (Performing with others is usually a lot more fun though! And easier.)

James Jacobs: To name just the most obvious examples of the kinds of demands placed on you on this album, there are two pieces in which you play violin and percussion simultaneously. How did you manage that?

LSJ: Bubamara [Milica Paranosic] is simply ankle bells and a passage with simultaneous pizzicato and theme – in the manner of a guitar accompanying a singer. The Laurie Anderson [an instrumental arrangement of her 2001 song Statue of Liberty] was a bit more complicated to realize – I wanted to have Tibetan singing bowls in my arrangement. In the end I devised a way of attaching a swinging mallet to my right wrist (which gives the whole arm extra weight) and leaving a heavier one on the table for a few left-hand gongs during string drones. Luckily the tune is in G minor allowing for open strings, and somehow it works.

One thing the pandemic did was make me realize it’s time to march to the beat of my own drum, not just figuratively, so I took Cuban foot percussion lessons in 2021 from Magdelys Savigne, the percussionist of the Cubanadian (I coined that) group Okan. I can now do a cascara with left foot, clave with right, and also play the violin! That was hard to learn.

However, I’ve clapped and tapped odd meters and polyrhythms forever with hands, or one foot (John Corigliano’s STOMP is dedicated to me) so ankle bells seemed a natural fit with something like Bubamara. She left it up to me to figure it out, so I decided on some pizzicato and bells, to help it sound like a one-woman Macedonian Roma campfire.

(More about STOMP below.)

JJ: There are three pieces on this album inspired by insects: ladybugs, fireflies and butterflies. Did you visualize these insects while playing these pieces?

LSJ: It’s a complete serendipitous coincidence – I find insects fascinating, and apparently those three composers do as well. Gabriela’s piece [Luciérnagas from Suite Mestiza by Gabriela Lena Frank] really feels like the night sky lighting up with those sweet creatures, and I think Valerie’s work [Danza de la Mariposa by Valerie Coleman] was begun by her imagining the similarities with the butterfly’s flutter and the sounds of the flute, for which it was originally written. As for Bubamara (ladybug), Milica assures me that a Serbian ladybug is quite aggressive and “she knows what she wants”. I’ve never quite seen one like that here, but then again, I’m not an aphid.

JJ: Jessica Meyer describes her piece Confronting the Sky as a “reflection on relationships”. Much of the piece is written in two voices and you do an extraordinary job of differentiating them so that they really do seem like two distinct personalities. I suppose in some ways this feat isn’t that different from playing a Bach fugue.

LSJ: I think we all have learned a great deal from Bach and his towering solo string works – and Jessica, also a violist, is no exception. The personas in her piece are well suited to linear voicing – sometimes even making one instrument sound like two or three very different folks.

JJ: Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Barber were all told that something they wrote for the violin was unplayable, and yet all those pieces continue to be played, which shows us how much we should trust certain self-appointed experts. Melissa Dunphy was told by one such expert that her composition Kommós was unplayable, and yet here it is on your album, a powerful work inspired by Greek tragedy. Did this piece feel cathartic to play?

LSJ: I have a sneaking suspicion that classical musicians often declare things unplayable through some strange need to feel superior to the composer, and, to put it bluntly, sheer laziness. There is nothing in Melissa’s piece that is even remotely impossible, so I can only imagine why that Curtis-trained violinist would have told her that.

Corigliano’s STOMP, which I mentioned earlier, was written for the Tchaikovsky Violin Competition. Gergiev told him it was unplayable so only when I made a live video of it did he admit it as the required piece. Sometimes composers ask us to do something completely new, and the answer is to sit down and figure out how, and work with them on it.

(John Corigliano wrote STOMP as the contest piece for the 2011 Tchaikovsky Competition in St. Petersburg. You will be able to hear Lara play it on WETA Classical on the November 19 episode of Center Stage from Wolf Trap, and you can see her perform it below. But you should also tune in November 19 when you can also hear her perform an earlier Corigliano composition, the 1963 Sonata with pianist Martin Kennedy.)

JJ: Not all of the music on she/her/hers is new. Intégration II was written in 1980 by the French-Canadian composer Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux, while the oldest music on the album was written by Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté, a wonderful composer with a fascinating story. How did you discover her music?

LSJ: Every Canadian musician grows up with her name – after an incredible early life in Russia, Paris, Berlin, Spain and Vienna, she settled in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and is a revered Canadian composer. I was shocked to find out that she is so little-known outside of Canada. She played both violin and piano and wrote some great music for both with an innate understanding of the instruments. Her 10 fabulously violinistic solo violin Caprices are based on observations and experiences from her own life.

JJ: Her Caprice no. 1, “The Sickness and the Clock”, was written in 1924, but thematically it feels sadly appropriate for the pandemic. How did it feel to play that piece?

LSJ: She aurally nails the despair and grief one feels helplessly watching a loved one die. I was fortunate not to have lost any people close to me to the pandemic. So many millions did, and this work felt empathetic to me.

JJ: Are there any other pieces or memories of the recording sessions for the album that linger for you?

LSJ: My engineer, Laura de Rover and I had a really good time. It was just the two of us, so after each session we’d cook something and drink wine and listen to all sorts of music, and later we also did the editing together (she is a singer/songwriter and even wrote a piece for the album).

JJ: There’s one line in the lyrics to the original version of Laurie Anderson’s Statue of Liberty that stands out: “Freedom is a scary thing - not many people really want it”. The political implications of that line are self-evident, but there are also creative implications. Many classical musicians I have met are scared of too much freedom, or don’t want it at all.

LSJ: I have met many of those classical musicians and I feel sorry for them. I would find it stifling and bone-crushingly boring to do the same thing over and over. Some are resistant to change even within their repertoire.

And frankly, I think that’s where we get our often-deserved reputation of classical music being tedious and dull. There is no way that players who don’t challenge themselves even occasionally can be truly creative, and that comes across to audiences.

I would encourage folks to listen and learn and try and ask and realize that there is a massive musical world out there – every bit of which we can learn from. And it’s all so interesting!

WETA Passport

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.