"Dwalin and Balin said: 'Excuse me, I left mine on the porch!' 'Just bring mine in with you!' said Thorin. They came back with viols as big as themselves, and with Thorin’s harp wrapped in a green cloth."

This passage in the first chapter of The Hobbit might be the first time many children encounter the word viols. Since all the characters mentioned are dwarves, then it seems reasonable to assume that the instrument Tolkien was describing was the bass viola da gamba, which at around forty inches high would indeed be almost as tall as the dwarves of Middle Earth. Tolkien provided no illustrations for this scene in which “Far over the misty mountains cold” was performed in Bilbo Baggins’ living room, so it falls to me to describe this instrument.

It’s larger than a guitar, though like a guitar it has six (sometimes seven!) strings as well as frets (the bars on the long neck on which the player places the fingers of their left hand to produce the desired pitch). (Unlike guitar frets which are inlaid metal, viol frets are made out of the same material as the strings - sheep gut, sorry - and are tied on so that they’re adjustable.) It’s a bit smaller than a cello, though like a cello the strings are arranged in an arc over a curved bridge near the bottom of the instrument, and it’s played with a bow. Unlike the cello bow, however, the viol bow is played underhand with the fingers directly touching the horsehair as well as the wooden stick. Thus the player is using a pulling motion to draw the sound out of the strings, giving the viol’s tone its characteristic “swell” and intimate quality (as opposed to the overhand grip which gives the player more control and greater volume.) The swelling waves of sound this produces creates a haunting effect that’s particularly noticeable when multiple viols play together.

The tuning of its strings is also akin to the guitar and lute, making it possible to play similar types of chords as those instruments, which the player produces not by strumming with the fingers but by a graceful sweep of the bow across the curvature of the strings, an effect exploited by many composers of the Baroque era.

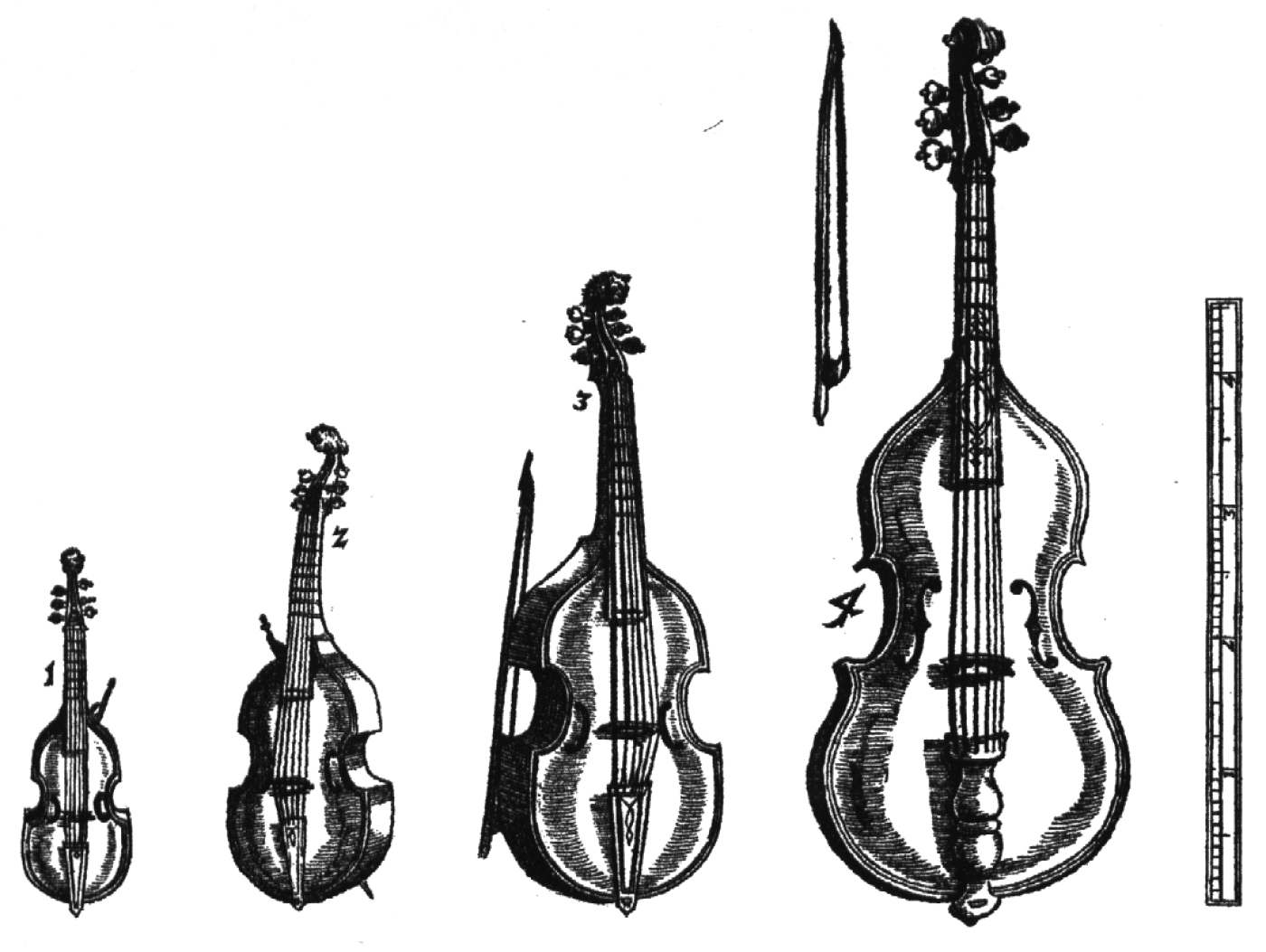

The bass viol of which I have been speaking is the most common size, but viols come in several other sizes as well, including the higher-pitch treble and alto (which are also played upright, resting on the leg, despite their being similar in size to a violin and viola), tenor, and a few variants of contrabass (played standing up, it’s the direct predecessor to the double bass. A frequently used term for the largest sizes of viol is violone.) A complete collection of all viol sizes is known as a chest of viols, which had their own piece of furniture to accommodate them, which could be found in many well-appointed aristocratic homes in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in England and France.

The hybrid nature of the viol has led to many theories as to its origin. Beyond determining that the viol and the guitar share a common direct ancestor in the vihuela, a fretted instrument popular in 15th century Spain that was made in both bowed and plucked versions, the only real explanation is that, throughout the last millennium, string instrument builders - aka luthiers - were constantly experimenting with different designs, and some of them were more successful than others. In any case the viol seems to have emerged in some form in the late 15th century and had died out by the late 18th century, and it spent over half that span as the predominant bowed string instrument of its time.

As I mentioned in my previous blog entry, The Story of the Bow, the viol became known as viola da gamba (Italian for “viol of the leg”) to distinguish it from members of the violin family, called viola da braccio (“viol of the arm”). Since the term violist has been claimed by players of the viola, the alto of the violin family (whose German name, incidentally, is Bratsche, derived from braccio), players of the viol are frequently called gambists.

One of the first types of composition written for an ensemble of viols (known as a viol consort) was the In Nomine, which took its name from a passage set to the words “in nomine Domini” from the Benedictus section of the Gloria Tibi Trinitas Mass by the 16th century English composer John Taverner. As was typical for this type of choral writing, one voice intones the notes of an ancient plainchant in long tones (known as the “cantus firmus”) while the other voices weave a kind of sonic tapestry around it.

It is not known who arranged this passage as an independent piece for viol consort, but whoever did is a very significant historical figure, because they played a large role in the development of chamber music. The In Nomine became a phenomenon that inspired many other composers to weave their own sonic tapestries around that same cantus firmus, in an unbroken tradition that lasted a century and a half all the way to Henry Purcell in the late 17th century. This in turn inspired composers to write other forms of music for viol consort, creating a rich body of work that remains one of England’s major contributions to music. These pieces would have been played in the living rooms of those lucky enough to afford a chest of viols.

But the In Nomine had an extra-musical significance as well. In nomine Domini means “in the name of the Lord.” At a time when anyone practicing a religion outside the Anglican Church could have been arrested and executed, the metaphor of a lone voice holding onto its steady faith, letting the noise of the world swirl around them without letting it tempt them to stray from their path, was powerful, a form of protest and resistance. Taverner himself was Lutheran, and one composer of several In Nomines was a Catholic, William Byrd; they were both technically guilty of heresy, and one can imagine that this form of composition expressed in music what they dared not speak in words. (This year marks the 400th anniversary of Byrd’s death, and one could argue that his death actually is something to celebrate because of its triumph: despite living in constant danger of persecution, he died a wealthy man in his 80s, universally acknowledged in his lifetime as the greatest English composer.)

It’s also possible that an In Nomine could have been used in the original production of one of Shakespeare’s last plays, The Winter’s Tale. Hermione, who had been posing as a statue after spending sixteen years in hiding, comes to life to the sound of music. Her first words are “You gods look down and from your sacred vials pour your graces upon my daughter’s head!” Many scholars believe that vials is a pun on viols, the instruments that are playing as she’s saying this, and certainly the metaphor of a lone voice keeping faith against all odds is extremely appropriate for this moment in that play. (It’s also likely that Shakespeare had the viol’s sound in mind when Benedict says in Much Ado About Nothing, “Is it not strange that sheeps’ guts should hale souls out of men’s bodies?”)

One particularly colorful contemporary of Shakespeare’s was Captain Tobias Hume, who made his living as a professional soldier with the Swedish and Russian armies but also found time to be one of the great trailblazers of viol writing, both as a solo instrument and as an instrument to accompany singing; Hume insisted that the viol was far better suited for that purpose than the lute, which earned him the enmity of John Dowland. He had a rather interesting sense of whimsy and humor; among his works is a song in praise of tobacco and a piece intended to be played by two people on one viol. In his work “Harke, harke” he became the first composer we know of to utilize the col legno technique whereby the player hits the wooden stick of the bow against the strings, an effect later used by Rossini, Berlioz, Saint-Saens, Mahler, Stravinsky and many others.

Meanwhile the viol was also becoming popular in France, where another groundbreaking viol composer became the star of the Parisian salons by the 1660s: Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe. He is credited with adding the seventh string to the bass viol and wrote hundreds of works for both solo viol and viol duet. In his later years he performed with his two daughters whom he trained to also be viol virtuosi, and was a celebrated teacher. His most famous pupil was Marin Marais, who became a court musician at Versailles and one of the leading figures of the French Baroque. (Marais had his own strange sense of humor; one of his pieces is a musical depiction of a bladder stone operation.) The relationship between Sainte-Colombe and Marais was the subject of the French 1991 film Tout les matin du monde, which won numerous awards and introduced the viola da gamba to audiences unaware of the instrument (even Roger Ebert in his review misidentified Marais as a “cellist”.) The film’s soundtrack was a best-seller, bestowing popular fame upon Jordi Savall, who arranged and performed the film’s score and is perhaps the greatest gambist of modern times.

That seventh string became a prominent feature of 18th-century viol writing. Johann Sebastian Bach made effective use of this extended range in the aria “Komm, susses Kreuz” from St. Matthew Passion, in which a frequent change in register is meant to convey the weight and burden of the cross. In the recitative “Mein Jesus schweigt” quickly rolled chords across all the strings effectively suggests the sound of the whip used to flog Jesus. Whereas in the St. John Passion the viol is used for its plaintive quality in evoking Jesus’ isolation on the brink of his death in the aria “Es ist vollbracht.”

The viol’s versatility is perhaps best illustrated in Bach’s three sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord. Each of the sonatas represents Bach’s three approaches to instrumental composition. The first sonata fulfills the canard that Bach’s music is infinitely adaptable; he later made two arrangements of the piece for different instruments. The gamba version isn’t necessarily superior to the later versions but it holds its own and works beautifully. The second sonata is a rare example of Bach composing in a more French manner where he really pays attention to tone color and the specific qualities of the two instruments and how they interact. The third sonata represents the opposite scenario from the first; no matter what instruments play it, it sounds like it was really meant for some imaginary orchestra Bach prefers to suggest than fully provide (his Italian Concerto is another example of this type of writing.) There have been several attempts made to turn the third gamba sonata into an actual concerto with orchestra, but that misses the point that Bach is showing us, that the viol has the ability to evoke several different musical attitudes and textures and spark the listener’s imagination.

It’s been frequently said that the viol was already “on its way out” by Bach’s time; the narrative usually has it that it was supplanted by the cello. They were actually never in competition. The viol family existed in its own separate universe from the violin family and it was always evident that it was the latter that was going to form the basis of the orchestra. This was made clear as far back as 1607, when Monteverdi called for ten members of the violin family to be used in his opera Orfeo. Joined by two contrabass viols, this marked the birth of the modern string section, and this 12-piece unit is employed frequently throughout the opera. The score also calls for three bass viols, but they are only used in two brief passages accompanying the spirits of the underworld. So we see that from the very beginning of orchestral writing, viols (except for the contrabass) were seen as a “special effect” instrument. Even at the peak of their popularity, viols occupied a rarified sphere, associated with the nobility, the supernatural, the divine, and death; they were frequently played at funerals. Whereas violins were the instruments that accompanied dancing and were played in daylight by mere mortals.

The last of the great gambists were Ludwig Christian Hesse, who worked with CPE Bach at the court of Frederick the Great in Berlin, and Carl Friedrich Abel, who worked with JC Bach in London, where they jointly established the city’s first subscription concerts. Luthiers continued their experiments, and two of them inspired works by major composers: the baryton added to the viol a set of strings that rang sympathetically and could also be played by the player’s left thumb; and the arpeggione was a hybrid of cello and guitar, with an overhand bow. Haydn learned to play the baryton and wrote 125 trios including the instrument at the behest of his employer; and Schubert wrote a famous sonata for the arpeggione that is usually heard today played on cello. After virtually disappearing in the 19th century, the viol itself began its long road to revival in the early 20th century.

In recent years there have been experiments in new music for the instrument, including electrifying it. But even in that realm the violin and cello have been more successful. Wherever the viol goes next, it has to respect its natural inclination as an instrument that likes to play with with its own kind and make people lean forward to listen to it - a unique voice that holds onto its special character and haunting intimacy, unshaken by the world swirling around it.

WETA Passport

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.