This article is the first in a series of my conversations with Washington, D.C.-based opera scholar, Saul Lilienstein, about the Verdi operas scheduled for broadcast this season on WETA Classical’s Opera Matinee Saturday afternoon feature. We’re delighted to hear Mr. Lilienstein’s insights into opera, many of which he has shared throughout the Washington, D.C. community through his involvement with professional arts organizations, universities and The Smithsonian. This conversation includes references to comments Mr. Lilienstein previously presented in his lecture series for Washington National Opera.

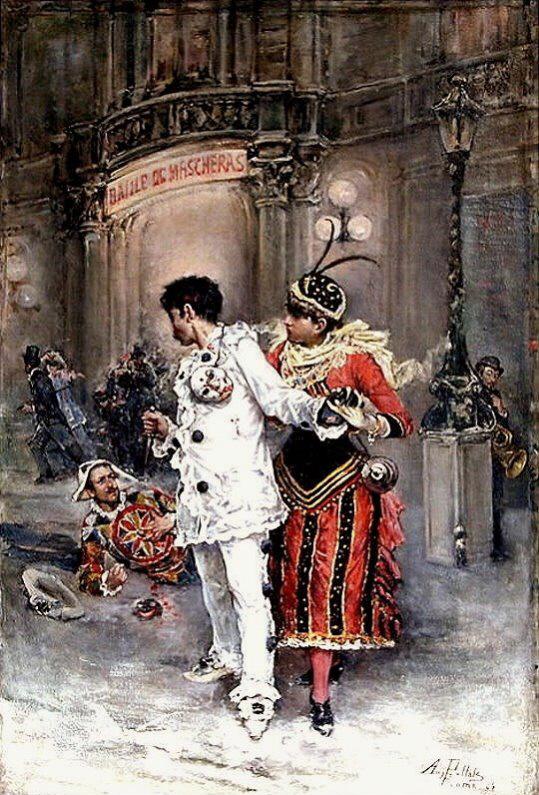

Linda Carducci: Let’s discuss Verdi’s middle-to-late career opera, Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball), based on a historic event – the assassination of King Gustav of Sweden during a masked ball by his political enemies at the Stockholm Opera House in 1792.

SL: Yes, it was an event that effected not only Sweden but France. Revolutionaries in France took notice of the Swedish assassination and just a year later the French executed Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. So although the cataclysmic events of 1792-1793 weren’t good for royalty, they provided very good source material for opera! Other 19th century composers, such as Daniel Auber and Saverio Mercadante, wrote operas on Gustav’s assassination before Verdi did so. Verdi’s version stemmed from a commission from the Teatro San Carlo in Naples 1857. He originally called it Gustavo III, and later, Una vendetta, and he was drawn to it because he felt he could do something different with it. But he encountered difficulties with Spanish authorities in Naples, who censored the libretto written by Antonio Somma; they objected to the staging of an assassination of a monarch, and were unsettled by political unrest in France and an assassination attempt on the life Napoleon III in France. If Verdi wants to mount this opera, the authorities said, he couldn’t include an assassination or masked ball, and Amelia would have to be Renato’s sister rather than his wife! Frustrated, Verdi took the opera to Rome. Roman authorities approved the plot, as long as the action was moved to someplace outside of Europe. So Verdi and Somma relocated the action from Stockholm to Colonial-era Boston, and the King became the “Governor of Boston”, who we’ll refer to by his name, Riccardo. And in Verdi’s and Somma’s version, the main plot involved a love affair between Riccardo and his friend Renato’s wife, Amelia, that led to Riccardo’s assassination.

LC: It’s an interesting choice to move the plot from Europe, where the original action took place and where Verdi lived and worked, to the “New World.” Was Verdi familiar with pre-Revolutionary America and colonial New England?

SL: Probably very little, but he specifically said that the Governor should “be a man who has seen something of the world and had a whiff of the Court of Louis XIV.” I think that the mismatch of a New England colonial setting and sophisticated music with a sense of the French court is why Un Ballo in Maschera isn’t considered as great as Verdi’s Rigoletto and La Traviata, or as beloved and known. But how rich it is! It’s one of my favorite Verdi operas!

LC: The title refers to a masked ball that occurs at the end of the opera. There are, however, other forms of disguises throughout the drama, not just at the ball.

SL: Disguises concealing motives and people are evident in every Act of this work. Here’s a hidden love affair between Riccardo and Amelia that leads the betrayed husband, Renato, to murder Riccardo. On the surface, Renato acts as confidante and friend to Riccardo, while secretly plotting his murder. Here are supporting characters who use humor to conceal, and maybe even distract us from, other characters’ sinister actions. And here’s a suspicious fortune-teller who may or may not be a criminal. Eventually, though, masks are removed.

LC: Yet even in his dramatic setting, Verdi interjects light-hearted moments to contrast with drama. You’ve noted that Verdi skillfully used light and dark – chiaroscuro -- elements in this opera.

SL: In the early years of Baroque painting, Italian painters used chiaroscuro – dramatic interplay of light and dark in the same painting to give volume and depth and heighten contrast. Interestingly, this technique occurred a few years after these same Italians invented opera – that magical interplay of music and drama that blends light and dark. In Un Ballo, Verdi blends light with dark, tragic with comic elements from the edges of the stage more so than any of his other operas. We hear it when Riccardo rhapsodizes about his love for Amelia in a passionate romanza while sinister sounds of conspirators can be heard. And Riccardo’s page, Oscar, a trouser role for coloratura, with supporting roles of Sam and Tom, inject levity and broad comedy right out of a French music hall (remember that Verdi loved Paris!). Ulrica, a mysterious fortune-teller, foretells of Riccardo’s death and cautions him to beware of a traitor disguised as a friend. Riccardo responses with a mixture of indifference and fear, but dismisses the prediction in a cavalier disregard for his danger that can be seen as a representation of the Old Regime just before the catastrophe of the French Revolution. The scene evolves to an intricate quintet that melds humor, fear and even laughter. Riccardo’s lead role in this quintet is an example of Verdi’s capacity for expressing a specific emotional state. In the early 20th century, one tenor performing this role inserted nervous laughter within this quintet, a performance tradition that is often continued.

Elsewhere, Verdi inserted a can-can in a direct parody – and clever nod – to Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld! And as Riccardo is assassinated in the finale, a delicate mazurka from the ball plays on. It’s a scene made all of the more tragic as Riccardo forgives his enemies and reveals that Amelia never violated her wedding vows to Renato. No other opera composer has killed off as many characters as Verdi. But not so often with such a light spirit and elegance!

LC: Let’s put the opera in its context among other Verdi operas. It’s considered middle-to-late career, and was composed after his spectacular trio of Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La Traviata, which were written in the short span of 1851-1853. He was at the height of his powers, acclaimed throughout Italy. Maybe it was a sense of confidence and his well-known admiration of Shakespeare that led him incorporate comedy into tragedy.

SL: Perhaps. His opera just before Un Ballo was Simon Boccanegra, a grim telling from the first note. The following work, La Forza del Destino, is a dramatic and tortured history of lovers torn apart by death and war. But with Un Ballo, we get a heighted and delightful mixture of dark and comic, a chiaroscuro.

LC: Verdi is known for his robust, often muscular orchestration, combined with moments of profound delicacy. In Un Ballo, in particular, he explores colors and styles, such as doubling of voice with instruments. I’m particularly struck by how the orchestra supports the beautiful love duet between Riccardo and Amelia in the second Act.

SL: His instrumental colors, textures and rhythms – collectively referred to as tinta – are a joy in this opera. Sometimes stark contrasts of color and light, sometimes a fusion of the two. He used tonal sounds from the orchestra to represent and mirror the action in a way that supports the characters without overpowering them. The introduction to Act II that you mention occurs at midnight on the outskirts of town. It’s a great mixture of dark, sensuous and sardonic, which Verdi described as a “sinfonia of strong and terrifying colors.” Against this dark setting, Amelia arrives alone in a troubled state to gather herbs to give her magical powers to withstand the torment of her love for Riccardo. Verdi set the scene with wisps of delicate woodwinds. When Riccardo arrives, the scene evolves to a beautiful love duet between Amelia and Riccardo in which the tortured lovers sing of remorse that gives way to ecstatic passion. Verdi portrays this scene so sensitively with unexpected changes of tempo, key and mood. The result, I think, is one of the most intimate and voluptuous love scenes in opera, certainly one of the most romantic surprises in all of Verdi. Never before or since did Verdi use the sexual intimacy of this duet in such a dramatic and musical way; here, it’s given the central position in the middle Act!

There’s a clever use of syncopation associated with the fortune-teller Ulrica, who is cast in a suspicious light. Maybe this rhythmic device is designed to represent her as an agitating force or as an outsider? And let’s not forget the chilling aria ”Eri tu” (You were the one who stained her soul). In it, Renato rages first at Amelia for her infidelity and then at Riccardo for seducing his wife. Cold fury supported by striking orchestration!

LC: Opera was undergoing an evolution (some say a revolution) at the time in Germany with the operas of Richard Wagner. When Un Ballo premiered in 1859, Wagner had already completed Das Rheingold and Die Walküre from his Ring cycle, as well as Tristan und Isolde. Do you see Wagner’s influence in Un Ballo?

SL: No, in fact Wagner’s music hadn’t been performed in Italy at the time Un Ballo was premiered. But the idea of creating a musical theme that recurs to represent an idea or person, a device Wagner employed, is used in Un Ballo. Look at the second scene of Act III: it opens with reference to an earlier moment in the opera. Verdi’s model, though, for that musical reminiscence was from France; specifically, the idée fixe device that Hector Berlioz used in his innovative Symphonie Fantastique.

LC: Un Ballo in Maschera premiered in Rome in 1859 to great success. But it was also the premiere of a battle cry from the audience for Italy’s unification.

SL: Yes. At this performance were audience shouts of “Viva Verdi!” for the first time. It gives the initials of Verdi’s name a new meaning -- “Vittorio Emmanuelle, Re d’Italia” (Victor Emanuel, King of Italy). It’s the Italians’ cry for unification of Italy’s various states into one Kingdom of Italy under King Vittorio and the ousting of Austrian rule, a movement known as Risorgimento. Although Un Ballo in Maschera is not a political opera, it’s been said that Verdi spoke to his audience as the soul of Italy.

Hear Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera on WETA Classical’s Opera Matinee, Saturday, November 23, 2024 at 1:00 pm (ET).

WETA Passport

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.